The Zannis weren’t show offs in the kitchen. Food was never about opulence or status. A dish would appear on the table because years ago you said you liked it, or someone would get up before dawn to buy porcini mushrooms from the market, which had arrived that morning from the countryside, fat brown stalks still clodded with earth.

Food was also a link to the family’s past in a region of central Italy known as Le Marche. Each time they gathered around the table, they would reminisce about the three Zanni sisters, their personalities, their quirks, and their vastly different styles of cooking. Ida, my mother in law was known for her superlative vincisgrassi, the lasagne of the Marche, and the patience with which she would fillet a fish or prepare a Galantina di Pollo, a de-boned chicken stuffed with a mixture of minced pork, minced veal, boiled eggs nutmeg, pistachios, Pecorino, and ham, which would be wrapped in a clean cloth, tied up with twine and poached in broth. Peppa, the eldest’s cooking had been the most rich and opulent, while the youngest sister, Bruna, who had been the least well off, and the only one of the three never to have left the hilltop town of Cupramontana where they were all born, would bulk up her ragù Marchigiano with sausages and cheaper cuts of meat, sometimes adding a stock cube for extra flavour.

Theirs was a language I neither recognised nor had grown up with, and I envied its power to gather the family around a table. In contrast, my Tuscan mother had never learned to cook (the children in her house were forbidden from setting foot in the kitchen) while mealtimes had been gloomy affairs, served by their maid, Dina, and eaten mostly in silence. It was considered vulgar to comment upon the food on one’s plate when she was growing up, let alone attempt to prepare it, with the result that my mother arrived in London in 1959 unable to boil an egg or even light a stove. Having escaped her stultifyingly bourgeois life in Italy, the last thing she wanted to do was to “waste” her life in the kitchen, though having three children in rapid succession meant she did eventually learn to put together a few half-remembered dishes from her own childhood whilst simultaneously availing herself of the many labour-saving convenience foods available in Seventies British supermarkets.

In the early days, listening in to Avi and our chefs discussing the menu, I used to feel wrong-footed; the restaurant was half mine, and yet I didn’t have that instinctive lexicon to draw upon when talking about food, even though I had been living in Rome when Avi and I first met, and over the years had become a reasonably competent cook. Yet, I still couldn’t say with adamantine certainty why a Ragù should never be matched with spaghetti, nor why whole tinned tomatoes were superior to chopped, nor could I identify the hero dishes associated with each of Italy’s twenty regions.

What I did have was a palate, along with some kind of ancestral memory of Italian food. Each time I ate a slice of San Daniele prosciutto, or a piece of torta della nonna stuffed with lemon-scented crema and pine nuts, or gnawed on a tough chicken leg alla Cacciatora, tangy with vinegar and rosemary, it was though I was consuming the dishes of my childhood. I felt the same intense emotion eating Italian food as I did when listening to the music of Fabrizio de André or reading Il Gattopardo in the original. A kind of quickening in my soul, a sense of homecoming, or belonging, as though the building blocks of my taste had been predetermined before birth.

Where did this epigenetic inheritance come from? My mother had a complicated relationship with Italy, escaping to London as soon as she could, and yet unlike many parents bringing up children in a new country, she thankfully didn’t slough off the language of her birth in an attempt to fit in. Those five years of speaking exclusively Italian at home before I started school, were her greatest gift to the writer I eventually became. Words weren’t fixed or nailed to the mast of a single idiom; and while my English remained more fluent than my Italian, I was constantly holding one language up against the other to see which better expressed what I was trying to communicate.

The other link we had with Italy as children were summers spent with my mother’s sister, our adored aunt Bettai. Unmarried, with no children of her own, Bettai would collect us from Fiumicino airport, and we would spend a couple of nights in her flat near the Vatican. At mealtimes, the family’s maid, Dina, who was still alive, would shuffle around the table serving giant breaded veal escalopes and fried potatoes from a silver tray, followed by peaches which we instinctively understood were to be eaten with a knife and fork.

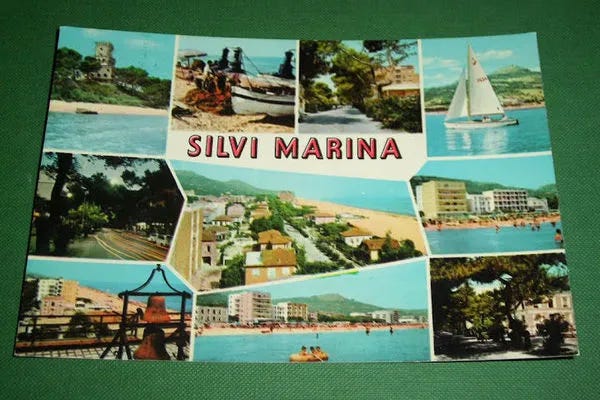

After a couple of days in Rome, we would drive, excruciatingly slowly, to the Adriatic coast, in Bettai’s white Fiat Panda, tailed by a line of honking cars with suitcases and rolls of bedding strapped on to their roof racks, and spend a month at the “Hotel Florida” in Silvi Marina. Bettai, like our mother, had never learned to cook, so it was pensione completa, with all three meals eaten in the hotel’s restaurant. Those holidays were the most enchanting of times; and fifty years later, they exist in my memory in a kind of vivid hyper-reality, in contrast to the perceived drabness of our London lives.

Everything about Italy was glamorous to us, even the faint smell of drains in the hotel courtyard, which of course wasn’t really a hotel, but a small, family-run pensione. I remember warm nights on the balcony, the three of us sitting in a row reading our books after dinner, bare feet up on the guardrail, a mosquito coil smouldering in the darkness. The agony of the two-hour wait after mealtimes before we were allowed to swim, and interminable siestas on our beds with drawing pads and wallets of “Carioca” felt pens, brighter and more juicy than English Magic Markers.

Sometimes, after dinner, we would leave the hotel for lo struscio, an amble along the seafront in our best clothes with all the other well-dressed holiday-makers, to eat a peculiar Italian dessert called Gelato agli Spaghetti. Vanilla ice-cream would be extruded through a ricer, then topped with an Amarena cherry “sugo” and dusted with desiccated coconut to resemble parmesan. None of us really liked it - we secretly preferred the Algida and Motta ice-cream from the hotel’s chest freezer - but we all pretended to, because we were competing with eachother as to who was the most “Italian”, even though the other children in the pensione called us le Inglesine.

I never did become an Italian. Not really. Even when I lived and worked in Rome as an adult, people continued to refer to me as l’inglesina, just as they had done in the courtyard of the Hotel Florida. And they were right to do so. Terroir, as it turns out, isn’t just about food or wine, while cos-playing a nationality doesn’t make you a product of that country. It's the place where you grow up that determines the language you speak, the way you present yourself to the world. It even conditions your unconscious responses to landscape. I’m sure it’s no accident that, as much as I love the Mediterranean, I am drawn to swim in winter in the English Channel, or that my heart thrills at the sight of a hedgerow in spring.

Our three children were raised in London, eating the Zanni way, though they have their father to thank for that, not me. I’m not saying I would have fed them Turkey Twizzlers, but I never believed elaborate meals with a primo, secondo and contorno were a hill worth dying on, especially on school nights or when they were tired or hungry. (In the end I am my mother’s daughter.) Avi, on the other hand wanted the food he cooked to feel like home, so that wherever they were in the world our children would find comfort and familiarity in it. And they do. For them, the taste of Italy is not a place. It is their father’s kitchen. Pasta at midnight after a long flight, chicken soup with parmesan and pastina when they are poorly, too much olive oil, which in the end is never too much olive oil.

And me? I might not have grown up in a family where three generations sat around a table breaking bread, yet being an outsider means I haven’t lost my wonder and enchantment at Italian food. Existing in two cultures can sometimes be uncomfortable, but it’s never boring. And, the irony is that after years of speaking Italian every day both at home and at work, strangers now comment on my excellent English. Apparently, in London, at least, I’m no longer an inglesina.

(Originally published on Scribehound)

Love this!